Trust in transparency

Do you know anyone saying their business is going great guns right now? If they are (probably on LinkedIn), do you trust them? I’ve been thinking a lot about the value of trust recently, and about two other ‘Ts’ – transparency and truth.

This was all kicked off by reading the new edition of Marcus Sheridan’s book They Ask, You Answer, which says you need to be the most trusted person in your market, willing to say what rivals don’t. It's about flooding customers with frankness and detail before a decision; then offering a menu of services so they can tailor their buy when they’re ready.

That suits my own philosophy. It prompted me to create an online tool to help people decide whether they need CFO in their growing business. Because if you don’t, well, it would be pretty awful for a recruiter to take you on as a client. In the long run, it’s much better to be trusted than to snatch engagements.

So let’s be transparent: assignments have been stop-start at the start of the autumn. I think most of you will recognise that truth, three-quarters of the way through a very uncertain 2025. Decision-makers are nervous. Deal-making is slow; PE exits ditto.

But that’s created time for other things. I’ve been cleaning my contacts database (and having some brilliant conversations as a result of checking in on people I haven't seen for ages); developing an education centre for the web site (to help answer clients questions); and working out what the market’s going to need as we head into 2026.

It’s got me thinking about what the purpose of a recruitment firm is, too. The optimum outcome in this business is people getting the job they want; and clients getting the finance execs they need. Our business drops out of that endgame – but I suspect in many recruitment firms (especially ones with big overheads) those two things are almost by-products of the process, not its objective.

In other words, if my outreach helps people build their career (or optimise their leadership teams) and I’m not directly involved – that’s fine. I trust that in the long run it demonstrates the value Pitch Hill puts on great outcomes for our clients. Meanwhile, spending time with, for example, the folks at the Institute for Turnaround (whose excellent conference I attended last month) gives me a sensitivity to what businesses need – and what finance opportunities are out there for candidates.

Sheridan’s mantra could draw on a much older one, from the movie Field of Dreams: “if you build it, they will come.” There’s a value in trust and transparency – it just takes longer to arrive than a snatched transaction.

- Ray Nicholls

Things to do...

Now...

Register directors.

18 November is the deadline for a bunch of measures in the ECCTA. Companies House need director verifications and a load of other registration issues sort by then. No time to waste!

Next...

Prep for the ERB.

The Employment Rights Bill looked like it might get watered down with Angela Rayner out of government. But embattled PM Kier Starmer can’t risk losing the unions. Get ready.

Later...

Check out PISCES.

The new system for trading privately held shares launches this autumn. Providers can help you set up trading events, creating liquidity and energising employee and director incentive schemes.

Lies, damned lies, and...

Carry on continuing?

The “uncertain 2025” we mentioned above is visible is all sorts of places. Geopolitics obviously; there’s a lot of new regulations; and the macroeconomic outlook is… well anyone’s guess. But take a look at what’s happening in the private equity world.

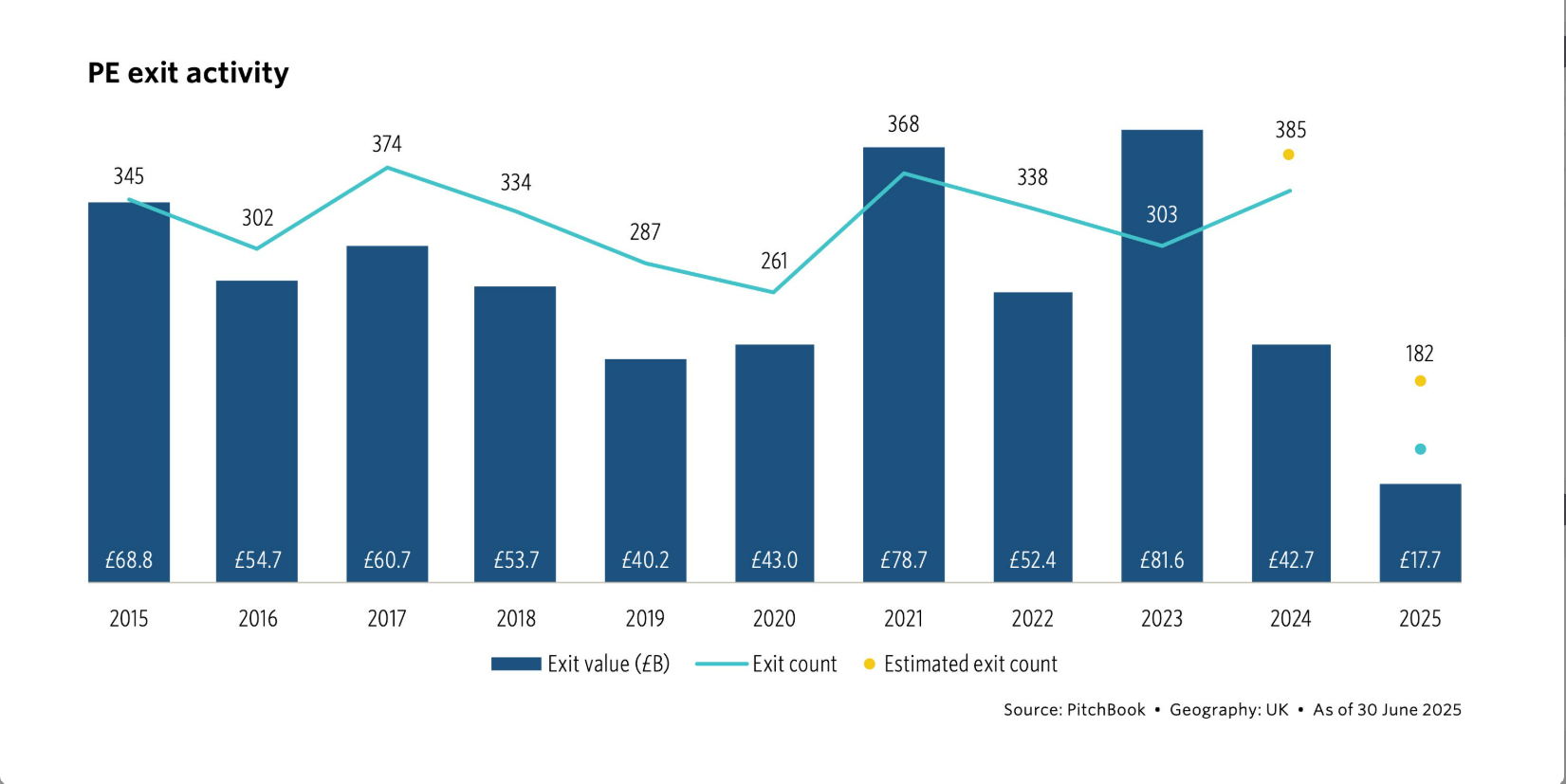

It’s been struggling for a while with aging assets. PE’s success over the years has damaged the attractiveness of the public markets… which were one of its main sources of exit capital. (Only five companies raised a total of £160m on the LSE in the first half of the year.) According to Pitchbook’s latest research: “Exits remain the [UK] industry’s weakest point, with H1 2025 exit value down 12.1% from H1 2024, itself over 50% below 2023 levels.” (See graph, above.)

Secondary buyouts have been the go-to strategy, but the whole point of PE is to conduct financial or operational transformation – and that’s tough at the second or third bite. (Just ask CFOs at long-held PE-backed businesses…)

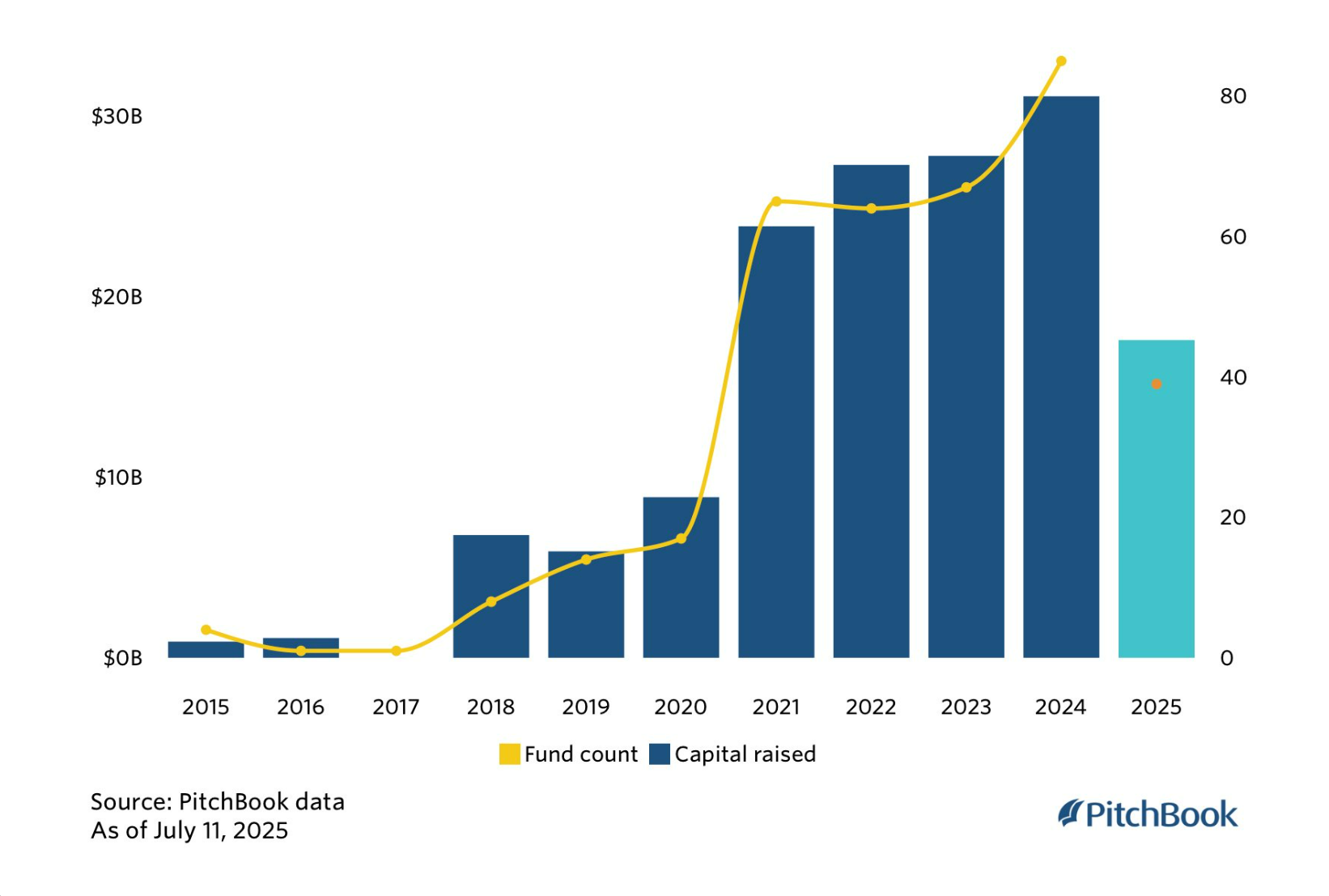

The new wheeze is “continuation funds” – effectively, PE funds selling companies they own to… their own vehicles (perhaps with a bit of fresh capital from elsewhere). And they have been on a tear of launches and fund-raising since 2021 (see Pitchbook's graph, below). Rolling into one of these funds looks like a liquidity event, but it’s not really an exit. According to investment bank Houlihan Lokey (quoted in the FT) about nine-in-ten investors have decided to cash out rather than roll over their capital when offered this kind of transaction.

The FT’s Katie Martin has a clear message: “private equity has held on to prize assets for longer over the years, squeezing more of the juice out of them, and leaving little for public market investors.” That has considerable implications for finance teams working in backed business; those running companies that do exit PE; and (I’m afraid to say) on the order books for the turnaround specialists. Heavily-juiced companies rarely fare well when conditions get more challenging…

On trend

AI scepticism is so 'in'

Time to roll out the Gartner hype cycle again. (Fun fact: it was invented by analyst Jackie Fenn, which means it really should have been christened the “Fenn Diagram.” No? OK...) Generative AI has definitely dropped into the trough of disillusionment, judging by conversations I’ve been having. Lots of people got extremely excited when they first played with ChatGPT; they imagined how it could transform processes; then realised that it wasn’t trustworthy enough to do any heavy lifting.

(The progress of Elon Musk’s self-driving cars is a perfect match: it’s been 18 months away for about a decade. It can do bits of driving fine; but it’s dangerous if unsupervised or facing the out-of-the-ordinary.)

Two trends here. First, CFOs have realised that AI isn’t going to be a revolution any time soon, and started to ask why even the last run of technologies for the finance function still haven’t delivered. “AI looks interesting, but it would be nice if the PowerBI we rolled out five years ago actually did what we hoped it would,” is a typical comment.

Second, techie people in finance functions are working out how AI applies to very specific cases – usually not even a whole process – to deliver meaningful productivity gains. Example: project costing – using AI to frame potential budget adjustments based on the impact of tariffs or possible interest rate changes. Or re-coding spreadsheet formulae.

Or try using ChatGPT to explain complex financial processes – such as Monte Carlo simulations – to non-financial managers. Seriously: it’s incredibly patient, and will keep on simplifying and creating analogies for the less financially literate, if they still don’t get it. It works!

One interesting datapoint is that a majority of companies seem to have developed some kind of governance model for AI… even though almost none of them are using AI for much beyond Copilot and ChatGPT. It’s telling that McKinsey’s analysis from March leads off: “Organizations are beginning to create the structures and processes that lead to meaningful value from gen AI.” “Structures and processes…” not "products and profits". A 2025 research report from MIT offers an even starker picture of GenAI adoption: “Despite $30–40 billion in enterprise investment into GenAI, this report uncovers a surprising result in that 95% of organizations are getting zero return.”

In short, it’s fine to be an AI sceptic right now. In a couple of years? Who knows. But if you’ve not dived in yet, try not to worry: most other execs and companies haven’t either. Now read on…

Words from the wise

AI: a careful industry?

We absolutely don’t want to write off AI. Far from it: even though more generative AI systems can’t even count (seriously, they’re essentially innumerate…), there’s a lot more to the technologies in development than ChatGPT poems or Midjourney images.

So let’s turn to an expert, one who brings the kind of reality check finance execs love when faced with hype: Rachel Coldicutt OBE. She’s a tech maven who’s at various times been plugged into the digital ethics and effectiveness debates in a number of Top Bodies including the BBC, the Royal Opera House and the OUP. Now she’s a consultant-cum-activist, running a couple of groups including Careful Industries.

And she’s been a source of sane analysis on issues like digital ID, cybersecurity and particularly AI. This, for example, is a great start when you’re in a conversation about AI: “We define AI in two ways. Technically, AI is a field of computer science that uses advanced methods of computing. Socially, AI is a set of extractive tools used to concentrate power and wealth.” Yeah, she’s a classic left-wing tech utopian (kind of), but that’s the kind of fix for the hype we all need.

“AI [is seen] as management sci-fi – a convenient fiction in which a new technology conveniently replaces the old digital systems, enables behavioural changes and implements infrastructural updates,” she writes. And her response is very FD-ish: “It can feel awkward to ask practical questions such as ‘what are you actually proposing?’ and ‘how will it work?’, but real knowledge requires detail and specificity rather than waves of shock and awe.”

You can find Coldicutt’s worth at Just enough Internet or on Bluesky, and she and colleagues run training on the reality of AI (and its implications for business and society).